RP McKenna from CounterPunch: Ted Downing and Troublemaker Anthropology

How “Yes, Sir” Necessarily Becomes “No, Sir”

Ted Downing and Troublemaker Anthropology

By BRIAN McKENNA

Censorship and suppression of one’s work are among the worst things that can happen to a writer, bureaucrat or cultural worker. Ted Downing, former Society for Applied Anthropology President (1985-87), experienced this and more. In 1995, Downing wrote an evaluation report describing the s evere social and environmental impacts likely to be suffered by Chile’s Pehuenche Indians from a proposed dam project underwritten by the World Bank. After his report was censored Downing demanded that the World Bank publicly disclose his findings. The Bank responded by threatening “a lawsuit garnering Downing’s assets, income and future salary if he disclosed the contents, findings and recommendations of his independent evaluation.” (Johnson and Garcia Downing). As a result of his whistleblowing, Downing was blacklisted from the World Bank after 13 years of consulting service.

“Personally, I was blackballed for 10 years for filing, what turned out to be 3 human rights violations charges against the IFC (private sector arm of The World Bank),” said Downing in an interview. “The experience left me only the devil’s alternative, to get involved in politics.” Literally.

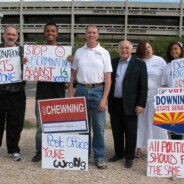

Downing went on to serve two terms in the Arizona legislature from 2003-2006. He rejected corporate contributions and collected hundreds of $5 contributions to qualify for public campaign financing. Downing introduced bills to protect the integrity of the election system, co-authoring a bill requiring hand count audits of electronic voting machines. He increased financial support for university and community college students, protected animal rights, improved energy efficiency and more. Eighty-six of Ted’s co-sponsored bills became law, a spectacular achievment for a Democrat in a Republican controlled legislature.

“Yes sir,” or “Yes, but,” or. . . .just “No!”

Many Ph.D.s never find solid employment in the academic world in this age of university downsizing and so offer their wares as evaluators, consultants or “applied anthropologists” to non-profits or the corporate world. A good many aim to foster social change but are unprepared for how best to do it. This is especially true for my field, anthropology which at this point in time has more Ph.D.s working in applied fields than the university.

Some years back Harvard anthropologist Kris Heggenhougen argued that the strength of anthropology in collaborating with other disciplines lies in saying, “yes, but. . .and to critically examine the decisive factors affecting peoples’ health including power, dominance and exploitation.” (Heggenhougen 1993)

Yes, but. . . . while that sounds good, more needs to be said.

First of all, we spend much more time saying “yes, sir” than “yes, but” in paid employment. This is necessary if we wish to stay employed. The workplace is a not a democracy but a hierarchy in which academic freedom does not apply. As Downing evinces, there are penalties for speaking one’s mind. Workers have to gauge the cultural politics in any given context so as to not unnecessarily risk censure, reprimand or worse.

Sometimes, like Downing, they must be prepared to simply say no sir and go with the consequences. Sometimes getting fired leads to new paths that can result in greater accomplishments. Much of it has to do with the right attitude.

Dr. Downing has the right attitude. He retains that probing, cantankerous spirit today. “I have no idea what ‘yes, but’ means having not read Heggenhougen,” he said. “The reference to ‘collaboration to other disciplines’ makes no sense to me – as I work on problems and am Undisciplined. I don’t think anyone would consider me a “yes man – which has helped and cursed me . . . . .But, I insist, fighting within a bureaucracy is part of being a good applied anything.”

In Downing’s anthropological journey, when “yes, but” didn’t work, he progressed, reluctantly, to “no, sir.” In fact this happens to many applied anthropologists but most do not have the resources, support or disciplinary guidance to assist them in their struggles. They might become whistleblowers but their careers suffer. And their stories are untold. We do not have a good accounting of how often this happens to anthropologists, but we need to learn more about this. In any case, resisting censorship is, as Downing says, “good applied” anthropology.

Like a Skilled Surgeon

“Good applied” anthropology harkens back to one of the masters of social science, Robert Lynd. In 1939, Lynd, author of the groun dbreaking Middletown studies (the first full bore ethnography of a U.S. city), wrote a book that is less well known, but just as important. Knowledge for What? The Place of Social Science in American Culture, is as relevant today as the moment he penned it.

In it he wrote that “[T]he role of the social sciences to be troublesome, to disconcert the habitual arrangements by which we manage to live along, and to demonstrate the possibility of change in more adequate directions . . . like that of a skilled surgeon, [social scientists need to] get us into immediate trouble in order to prevent our present troubles from becoming even more dangerous. In a culture in which power is normally held by the few and used offensively and defensively to bolster their instant adv antage within the status quo, the role of such a constructive troublemaker is scarcely inviting.”

“Troublemaker” is of course the pejorative term emanating from within t he dominant culture, targeting those who refuse to keep quiet in the face of injustice. “Yes but” is an ample part of their vocabulary. Anthropologist Barbara Johnston has wr itten about the work of being an anthropological troublemaker, especially in relation to doing environmental justice work. But she warns about associated risks. Environmental justice work “requires confronting, challenging and changing power structures.” When someone is involved in this work, says Johnston, “backlash is inevitable.”

“When environmental justice work involves advocacy and action – confrontational politics – a number of professional bridges are burned. . . .’Cause-oriented’ anthropology suggests people who make trouble. Troublemakers are celebrated in this discipline when t heir cause succeeds and justice prevails. But often ‘justice’ is elusive, success is hard to gauge, and action results in unforeseen adverse consequences. (Johnston: 2001, 8).

Because most anthropologists usually enter organizations as change agent s of some kind they need to be aware that they are especially at risk of being labeled a “troublemaker” at any time. If the label sticks it can lead not only to getting fired; it also can lead to a vicious form of bullying that can make one’s life unbearable.

Beware of the Mobbers

Anthropologist Noa Davenport knows this very well. In 1999 she coauthored a book with two other professionals called, “Mobbing, Emotional Abuse in the American Workplace, (1999). In the book’s forward Davenport and her colleagues noted, “This book came about because all three of us, in different organizations, experienced a workplace phenomenon that had profound effects on our well-being. Through humiliation, harassment, and unjustified accusations, we experienced emotional abuse that forced us out of the workplace.” Often the mobbing begins soon after the professional challenged a superior in some area. In other words, it’s often a “yes , but” interrogative. Today Davenport conducts workshops on mobbing and counsels people who have experienced such abuse. She turned her private suffering into a public issue and has advanced the culture.

In my research, “mobbing” has a great deal of unconscious group behavior associated with it. To understand it one must research the realms of psychoanalysis and group dynamics (Bion 1961, Armstrong et al 2005, Grotstein 2007). Often the abuse had the tacit approval of upper management who themselves are often behind it.

All terrains of employment in capitalist culture operate in a sea of conflict. For a critical applied anthropologist then, one is in dangerous waters from the first day on the job. As Kincheloe and McLaren underscore, critical ethnographers need to critically analyze how larger domains of power, including global and local capital, define one’s job and inhibit the possibilities of social science practice.

In the applied field, anthropologists are always trying to discern the location of what I call “the line of unfreedom,” the place where speaking up may cause reaction. Here’s a story from a veteran medical anthropologist that illustrates the pressures to conform to the “yes sir.”

“I’ve recently been eased off of a multi-million dollar grant that I co-wrote and am (supposed to be) the co-investigator on. My 5 year participation was cut off at year 1 by the Primary Investigator who was getting really nervous about w hat affiliating with me would do to his career. In a nutshell, I wrote a paper that he thought would offend his superiors and so didn’t want to have any links to me anymore. So he revised the budget and cut me out – without actually telling me until about 9 months into year 1 – and only finally because I directly inquired as to where my subcontract for years 2-5 had gotten to. Ultimately he’s the PI. He was the MD, I was the PhD. He was the insider at the ‘very large integrated healthcare system’ where the research is sited, I am not. So yes, he has decision making power – yes he could do that. Of course, that doesn’t make it ‘right’, but that’s how it is. Ironically, the higher ups liked the paper, which was really quite non-threatening.”

What would happen if this applied anthropologist made a work issue over this? He won’t. From experience he knows that it might not turn out well.

On the Job Which are You First: Employee, Professional, or Citizen?

Indeed, as I tell students in my “Doing Anthropology” course, there is an inevitable and permanent tension between three key aspects of “applied” work as: 1) an employee, 2) a professional and 3) a citizen. As an employee you sell your labor power to an employer. As a professional anthropologist you seek to abide by the goals, rules and20ethics of your discipline. As a citizen you are most interested in advancing democracy and public education. These subject positions conflict and overlap in numerous ways. But one can be sure that an employer is more interested in your value as an employee than a citizen.

I teach the Ted Downing story as an instructive for students own applied work. Like Downing, applied anthropologists have to be prepared to travel the road from “yes, but,” to “no, sir” in order to better serve the public interest. Unions are a vital part of this work, as is a keen awareness of how workers are proletarianized. Harry Braverman’s “Labor and Monopoly Capital” is a core text.

David Price continues to catalogue the perils of activist applied anthropologists, demonstrating how, in the 1930s through 1970s, they were subject to surveillance, marginalization and worse for their work. Anthropologist Mich ael Blim, in summarizing the Price book concludes, “Emerson’s adage that all it takes for evil to triumph is th at good people do nothing is here confirmed. Based on Price’s book, one might also add: ‘if you try to change your society, trust not your state, your university, or your profession.’”

“I am not sure the issue is simply that anthropologists are ‘not sufficiently educated about how to protect themselves when challenging authority’ – as that assumes that historically our anthropological teachers have the means and experience to educate their students,” said Barbara Johnston. Johnston said that anthropology faculty, in general, do not have the “seasoned understanding of power and backlash,” as it occurs in the non-academic world. This is so, she said, because they are still immersed in the “generic disciplinary reality of the ivory tower cocoon.” She argues that “ political naïveté is built into the dependency relationship between the discipline and the university structures that sustain the discipline.”

It’s an uphill battle. As Henry Giroux discusses in his writings, universities are turning into military-academic-industrial complexes where hierarchy is more entrenched and emboldened. Academics need to model “good applied” anthropology in their own workplaces (the knowledge factories of higher education) to be more convincing to their students. So how do we better protect ourselves in a harsh work environment?

Downing says, “Telling the truth is the most important thing – scientific credibility is critical. I document my reports with hundreds of references pointing directly to documents and footnotes. No embellishment – extra adverbs or adjectives – use the words of the documents. Facts, numbers, uncertainties, etc. Good science is your best defense as an activist. If your methodology is approved ahead of20time…and leads to an unexpected result – you are on good grounds. Good science gains respect, which becomes a shield….but not impermeable. Keep close to the overall organizational objectives of your clien t or organization – in the case of the World Bank, poverty alleviation.”

Downing, who is today a research professor of Social Development at the University of Arizona, said, “Whistleblowing is a last resort – since once it is done, your effectiveness as an internal change agent – moving the organization in the direction that it needs to go – is finished. I always feel a sense of personal failure when I had to take that last step. It was quite painful. There are other ways t o release information to the outside without blowing the whistle. For example, a freedom of information request or demand for an open meeting may crack opens an issue without the need for self-destruction.”

“I learned this during my two terms as a State lawmaker. And, above all, maintain a sense of humor on your self-importance. Aw ards are not given and statutes are not erected to whistleblowers!”

“I have been booted out of several count ries and organizations,” said Downing. “And be assured, the minute a whistle is blown, any weakness in your scientific and professional abilities will be questioned. It is a last resort after you have tried your best to change the organization. I have 3 feet of internal correspondence on the Pangue case going on for over a year before I field my first human rights violation charges against the World Bank (IFC) – trying to set things right so the Pehuenche Indians would not be harmed.”

Still, Barbara Johnston is not optimistic about academic culture’s abilities to prepare students for the perils of non-academic applied work. In an interview she said that the “ever-expanding continuum of engagement,” that is currently underway in anthropology will likely result in more censorship and backlash against applied anthropologists.

Academic Culture Trivializes Activist Work

Johnston points out that academic culture “trivializes the importance of this work,” while, at the same time, the engaged anthropologist struggles to find disciplinary support in dealing with backlash, which can range from papers that cannot be=2 0published (and thus cannot advance careers) to disinformation campaigns, character assaults, threats, even murder. She cites the execution of Colombian anthropologist in 1999 after studying displaced persons from a proposed energy development. He was shot by three masked gunmen at a faculty meeting. But the more common forms of retribution and retaliation come in the form of lost jobs, lost careers and lost health.

“While anthropology is a powerful social persona (in Hollywood, public consciousness, legally mandated reviews, etc.) in terms of numbers, it is a very minor discipline. The AAA has only about 11,000 member s compared to the American Economic Association with 21,000, or the American Psychological Association with over 150,000. This means that when it comes to power (who gets the most research grants, who gets to serve as the dominant social science voice in the corridors of power, etc), anthropology is a very minor afterthought.”

And yet there is much room for resistance, she adds.

“We have an unusual power because as a social personality anthropology/ists have captured the public imagination. There is a cachet to the title, to the opinions emanating from An Anthropologist.’ So backlash is not only a matter of an unprepared, unforeseen, poorly played hand, but also a matter of threat, and how be st to silence that threat. Anthropology is a very loud mosquito buzzing around the head at night. There is a lot of power there.”

Indeed, as Rylko-Bauer and Singer (2006) argue, the historical successes of “pragmatic engagement” must be reclaimed for the 21st century. “For applied anthropologists, the commitment to action is a given; the challenge lies in continuing to find ways of acting more effectively and ethically while linking the specificity of local problem solving to larger sociopolitical contexts.”

“Yes, but,” is only one way to act. It’s often not effective. In response to Heggenhougen’s challenge, we need to become better prepared to support colleagues who find themselves in circ umstances where, “no, but,” is where they must go.

A version of this article was originally published in the Society for Applied Anthropology Newsletter, Vol. 19:3, Tim Wallace, editor, August 2008

Brian McKenna lives in Michigan. He can be reached at: mckenna193@aol.com

References

Armstrong D., Lawrence W., Young R.

2005 Group Relations: An Introduction. London:Tavistock. Onlinebook:

http://human-nature.com/rmyoung/papers/paper99.html

Bion, W. R.

1961 Experiences in Groups. London:Tavistock.

Blim Michael

2007 Review of “Threatening Anthropology: McCarthyism and the FBI’s Surveillance of Activist Anthropologists,” Logos: A Journal of Modern Society and Culture 6:3.

See: http://www.logosjournal.com/issue_6.3/blim_printable.htm

Davenport, NZ, Schwartz RD, Elliot GP .

2005 Mobbing: Emotional Abuse in the American Workplace. Collins, IA: Civil Society Publishin g.

Downing, Theodore,

2008 See website for professional profile and writings at www.ted-downing.com

Giroux, Henry

2007 The University in Chains: Confronting the Military-Industrial-Academic Complex. Boulder:Paradigm

Heggenhougen H. K.

1984 Will Primary Health Care be Allowed to Succeed? Social Science and Medicine 19 (3):217-224.

1993 PHC and Anthropology: Challenges and Opportuni ties.

Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 1993, 17:281-289.

Johnston, Barbara

2004 “The Pehuenche: Human Rights, the Environment, and Hydrodevelopment on the Biobio River, Chile” by Barbara Rose Johnston and Carmen Garcia-Downing in Indigenous Peoples, Development and Environment edited by Harvey Feit and Mario Blaser (Zed Books). 2004:211-231.

Grotstein, James S.

2007 A Beam of Intense Darkness, Wilfred Bion’s Legacy to Psychoanalysis. London:Karnac.

Johnston, Barbara

2001 “Anthropology and Environmental Justice: Analysts, Advocates, Activists and Troublemakers” by Barbara Rose Johnston, in Anthropology and the Environment, Carole Crumley, ed. (Walnut Creek: Alta Mira) 2001:132-149.

Kincheloe, Joe and Peter McLaren

1994 Rethinking Critical Theory and Qualitative Research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Norman Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln, eds. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

McKenna, Brian

2008 “Melanoma Whitewash: Millions at Risk of Injury or Death because of Sunscreen Deceptions,” in “Killer Commodities: Public Health and the Corporate Production of Harm,” Merrill Singer and Hans Baer, eds., AltaMira Press

Price, David

2004 Threatening Anthropology McCarthyism and the FBI’s Surveillance of Activist Anthropologists. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rylko-Bauer, Barbara, Singer, Merrill and Willigen, john van

2006 Reclaiming Applied Anthropology: Its Past, Present, and Future. American Anthropologist; Mar 2006; 108, 1; Research Library

Tuesday, July 7, 2009